From Object to Process: Viewing the Moon Rock, Mixing with Foam and Fog

Marcel Finke

1970. Over the course of six months, about 80,000 people per day queued to take a brief look at a simple piece of stone. They lined up for hours in anticipation of seeing a greyish rock sample the size of a fist. The visitors barged their way through the crowded building before they were streamed past the lithic specimen, catching a glimpse and being pushed out of the exhibition space soon afterwards. At the end of its display, more than 18 million visitors had paid a call on that geological object. Why the fuss, what did they see?

Of course, the exhibit was not an ordinary chunk of rock, as its place of origin was about 384,400 kilometres away from Earth. The object of attraction came from the moon, and it had been collected and brought to our planet by the Apollo 12 mission in November 1969. The lunar rock with the sample number 12055 was part of the US-American pavilion at the world’s fair in Osaka (EXPO ’70), which took place from March to September 1970. As the centrepiece of the section “Space Exploration”, the stone from the moon epitomized a certain exhibition strategy. The NASA Public Affairs Office together with the U.S. Information Agency placed great value on presenting authentic artifacts from recent space missions. They focussed on showing recovered items of hardware and equipment such as lunar modules, space capsules and suits as well as real stuff from outer space. In the Osaka exposition and on other occasions, these objects served many purposes: for instance, they were meant to show the accomplishments of NASA’s manned space programme, to display the openness of US-American engineering, to attest to the nation’s scientific preeminence and technological capability in the service of all mankind, to demonstrate national values and the goodwill of U.S. policy, to support domestic and international relations, and to function as a means of cultural diplomacy. In order to be convincing, the exhibits had to be real – and surely there is no-thing more real than a rock. Thus, the moon rock was both solid proof of the lunar landing and an “instrument of soft power” (Teasel Muir-Harmony).

While only four people had actually set foot on the moon before, the intention was to put the 18 million visitors of the exhibit as closely in touch with the “real” as possible. But so far and no further, as the lunar rock sample was at once both near and beyond reach. The precious souvenir from outer space was there for all to see, yet thoroughly detached from the curious crowd. It was isolated and shut up in a futuristic cabinet made of anodized aluminium and fire-resistant Pyrex glass, being staged in utter aloofness. Within its container, the 3.2-billion-years-old extra-terrestrial stone was enclosed in an artificial, protective atmosphere in order to keep it untouched by earthly factors. Shrouded in its conditioned show-case filled with pure dry nitrogen, the “real” geological specimen from the moon remained other-worldly, being secluded from the climatic and ecological reality of the viewers and excluded from any exchange with their environment. Auratically illuminated from above and resting on a curved stainless-steel holder, sample 12055 was presented like a “kind of elegant piece of jewellery”, as Jack Masey, chief exhibition designer of the U.S. pavilion, remarked. A different association has been made by art historian Monika Wagner, who pointed out that the lunar rock was mounted like a relic of the space race in some sort of high-tech monstrance, turning the visitors into modern-day pilgrims eager to receive visual evidence from another world.

12055: a literally rock-solid object; with distinct and stable boundaries; existing for aeons; inert and enduring; movable, yet not moving; locked in its impermeable glass shell under special atmospheric conditions; isolated from its surroundings and cut off from any environmental relation; accessible to the eye alone and staged for visual consumption; withdrawn from the visitors in a state of over-againstness. In a way, the moon rock had been turned into an extra-terrestrial cousin of Graham Harman’s alleged “vacuum-sealed objects”. In the wider context of EXPO ’70, however, the exhibition of the stone was somewhat anachronistic. On the one hand, the lunar rock embodied the main official thrust of the Osaka world exposition, namely its techno-utopian and optimistic stance. As material evidence of a distant and only recently conquered place, it testified to the possibilities of advanced science and engineering. In this regard, the stone from the moon resonated well with the motto of EXPO ’70: “Progress and Harmony for Mankind”. Despite its crude and archaic appearance, the lunar rock shared in the positive visions of the future, expressing faith in a peaceful application of technology for the advancement of society and the improvement of global coexistence. On the other hand, it remained a foreign object, insofar as it was at odds with the more process-oriented focus of EXPO ’70. Instead of displaying concrete things and manufactured goods, the Osaka world fair programmatically championed the creation and experience of events and multi-sensory environments. Accordingly, executive planner Kenzō Tange called it a “festival” rather than an exposition. In the light of the EXPO’s performative and participatory character as well as its emphasis on systems, immersion, and exchange, the encased and dead still lunar rock, in all its solidity and seclusion, appeared to be the very antithesis turned into stone.

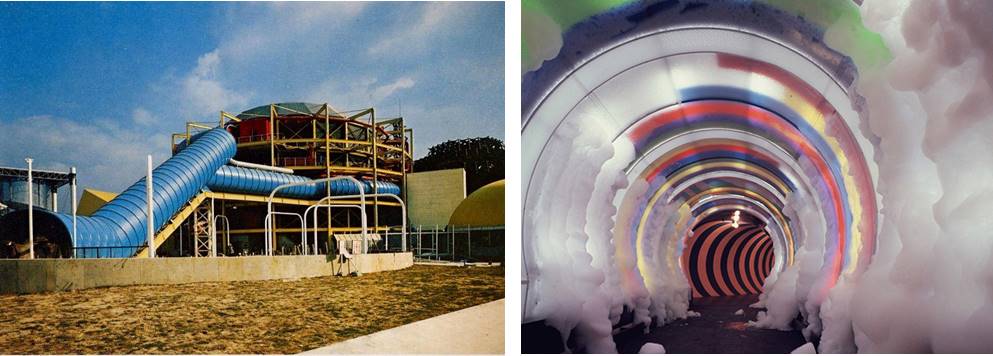

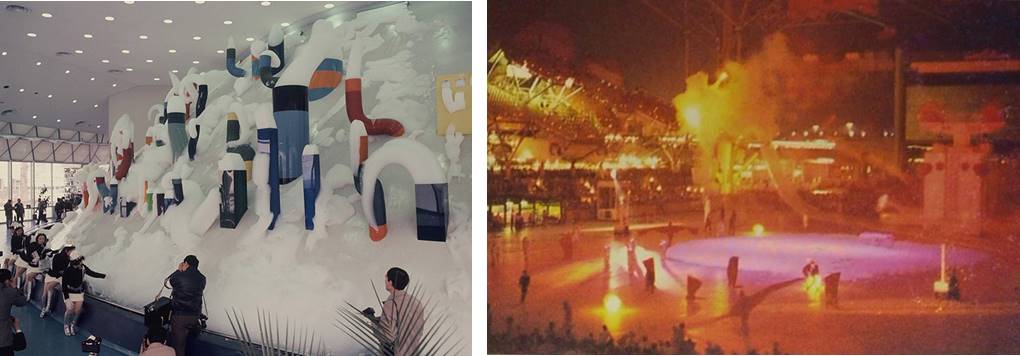

At other venues of the Osaka fair grounds, the exhibits were much more fluid and processual. Various attractions made use of liquid foam and fog, thus staging materials in action rather than displaying inert objects. Take, for instance, the corporate pavilion of the Mitsui Group. The building with its pipes, steel skeleton structure, and tank-like dome had the industrial look of a gigantic petrochemical plant, as one of the information brochures stated. There was, however, another obvious association, namely the reference to space travel. Its architecture evoked notions of “futuristic moon colonies” (Pieter van Wesemael), which was in tune with the interior and programme of the pavilion. The main part of the building was called “Space Revue Dome” and presented a high-tech multimedia environment that offered a “Trip into Outer Space and the World of Creation”. Before the visitors entered this “cybernetic staging” and “endless happening system”, as chief designer Katsuhiro Yamaguchi described it, they had to pass through a colourful foam tunnel. The tunnel was realised by Gutai artist Toshio Yoshida, who had been using soap suds as an artistic material since 1965. Froth oozed from perforations in the acrylic-glass walls and grew into the walkway, thus slowly narrowing the passage. As the visitors moved towards the spectacle of the “Space Review Dome”, they came into contact with the soft and evanescent materialisations of the ongoing aphrogenic process; they could touch, hear, and smell the foam, play with it, blow or carry it away, and so on.

Another example was the enormous foam installation in the entrance hall of the pavilion erected by the Japan Chemical Industry Association. Advertised as a “Chemical Fantasia-land”, among other attractions the building presented a kind of foam-fall, which was 9 meters high and 28 meters wide. It consisted of an inclined plane studded with chimney-like forms made of colourful plastic, which emitted cheerful and gentle accretions of froth. Following the call of gravity, portions of the foam eventually flowed down the slope, gathering in the ditch at the bottom, where they piled up into sudsy mountains. The visitors were allowed to touch these ephemeral formations, dipping their hands into the fluffy mass as if it was a bubble bath. Occasionally, clouds of foam hovered in the hall, being blown around by the ventilation system. Even more froth floated through the EXPO air due to the foam-storm that formed the grand finale of the Gutai Art Festival. In the closing sequence of this theatrical extravaganza, the Festival Plaza was flooded with vast amounts of the sudsy substance produced by two fire engines. The participants of the performances that had been staged previously reunited and plunged into the foam-scape, immersing themselves in a playful and turbulent bubble palooza.

The most famous exhibit presenting a fluid material process at EXPO ’70 was part of the Pepsi Pavilion. At this venue, mist was the main actor rather than foam. In cooperation with the US-American group Experiments in Art and Technology, Japanese artist Fujiko Nakaya installed the first of her so-called “fog sculptures” on the exterior of the dome-shaped building. With the help of a meteorological monitoring device, an air pressure and pipe system, and 2,520 nozzles she atomised water into microscopic, free-floating droplets, thus producing volatile wafts of mist that enshrouded the pavilion and involved its visitors. Due to variable weather conditions and environmental circumstances, the fog was constantly changing, too, showing fleeting nephogenic formations and the fluctuations of its own density and contours. Nakaya considered the atmosphere and the aerial fluxes as a “dynamic mould” that (trans-)formed the fog sculpture incessantly; to her, the mist “danced with the wind” in real-time. In a way, the visitors were also able to join in this dance; they could mix with the fog, yet could hardly tell where it began or ended. And if the meteorological conditions changed unfavourably or the technical equipment was switched off, the mist quickly cleared and ceased to exist.

Foam and fog: fluid materialisations of aphrogenic and nephogenic processes; dynamic and devoid of clear-cut boundaries; ephemeral and open-ended; responsive to changes in the atmospheric conditions; reaching out into their vicinity; interdependent on environmental relations; allowing the visitor’s body to participate in the material goings-on and to enjoy multi-sensual experiences. By getting involved with foam and fog, we are reminded that the “world of materials” (Tim Ingold) is not sealed off and “over there”; on the contrary, we are inescapably immersed in it. The frothy and misty productions draw our attention to the fact that materials are on the move and spread everywhere; they are stuff in action that can barely be contained within man-made confines. In a sense, we are still more familiar with rocks from outer space than with such mundane materialisations as foam and fog. In order to arrive at a fuller understanding, we might therefore leave objects for a while, supplementing reflections on their hard and dry materiality with an epistemology and “material literacy” (Ann-Sophie Lehmann) of the fluid.